Martial Arts Film Fight Way to Top of Building

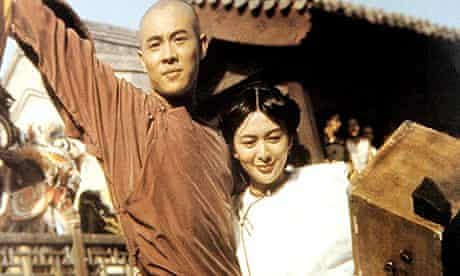

ten. One time Upon a Time in China

The movie that kicking-started Hong Kong cinema'southward kung-fu renaissance and launched Jet Li towards a hereafter of substandard western action movies. Its bailiwick was already well known to local audiences: Wong Fei-hung was a real person: a turn-of-the-century martial arts master and healer who's go something of a folk hero. Similar Sherlock Holmes or Robin Hood, he'd been portrayed many times earlier. Jackie Chan played him in Drunken Main, and a long-running Wong Fei-hung film series during the 1950s and 60s gave roles to the fathers of Bruce Lee and Yuen Wo-ping, among many others.

Transposed to 1990s Hong Kong, with the handover from British to Chinese sovereignty on the horizon, this story of a Chinese rebel fighting oppressive colonialist powers had extra resonance. Its British and American baddies are cartoonishly demonised, and the plot is often convoluted to the point of impenetrability, admittedly, simply what this film importantly provides is dazzling, colourful, kinetic, epic, pre-CGI spectacle. Managing director Tsui Hark, schooled in both the US and Hong Kong, fills the screen with motility and energy. The wire-assisted fight scenes – choreographed by Yuen Wo-ping, inevitably – are ingeniously staged. Earthbound reality is left far backside.

And Li is simply incredible. He's got gravitas every bit an histrion, but when he's in activity, he really takes some beating. He does information technology all: fighting with hands, feet, sticks, poles, umbrellas. He kills one baddie with a bullet – without using a gun. But Li is a gymnast, too, pirouetting and somersaulting across the screen with the agility of a cat. He'south surely the most graceful martial artist out there. Those skills come up to comport in a jubilantly athletic final duel, which takes place in a warehouse conveniently full of bamboo ladders. Information technology's 1 of the most celebrated sequences in martial arts movies, and it leaves yous wanting more, of which in that location is plenty: they made four sequels in the adjacent two years. Steve Rose

nine. Yojimbo

Akira Kurosawa drew upon American pulp sources for Yojimbo's plot, principally the Hollywood western but likewise Dashiell Hammett'southward broken-city melodrama The Dain Curse. Here a alone, probably disgraced, certainly hungry samurai (Toshiro Mifune, the Wolf to Kurosawa's Emperor) wanders into a boondocks where ii factions are in eternal conflict, glaring at one another from their matching headquarters on opposite sides of the town's broad, western-like master street. Since each faction lacks a distinguished warrior with whose aid they might tip the balance of ability in their favour, they each badly want the newcomer on their side, something the samurai figures out within moments, and exploits throughout the pic.

As the power games play out to their nihilistic, corpse-high-strung conclusion, Kurosawa demonstrates a mastery of his medium in virtually every frame. His sense of spatial relations is beyond compare: panels in interior walls slide away to reveal whole outside street-scapes and crowd scenes perfectly framed within the smaller new frame. Intimate conversations take place as a turbulent skirmish rages in the deep groundwork center-screen, between the talkers' faces in the foreground. And what faces! From the moronic warrior with the M-shaped unibrow and the giant wielding a huge mallet to Mifune's increasingly battered countenance, sardonic, cynical and ever defiant, every single face up is at in one case a mural and an ballsy poem unto itself.

Forth with all that comes Kurosawa's furious visual energy, his virtuoso choreography of moving camera and bodies of warring men; and his talent for adding enriching layers of kinetic, elemental motility – rain falling, leaves or fume blowing in the unceasing winds – to the violence already in play. Yojimbo led to the Italian A Fistful of Dollars, which in time completely remade the American western, completing a circle of international cultural commutation that foreshadows a give-and-take among international filmmakers that nosotros take for granted today. John Patterson

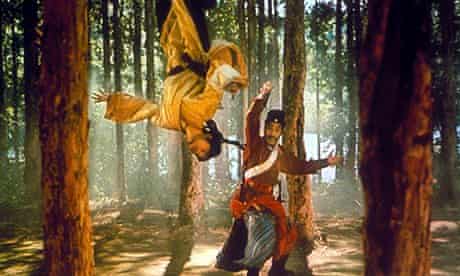

8. A Affect of Zen

Nosotros have A Touch of Zen to thank for Harvey Weinstein'southward interest in Asian cinema; information technology was later on Quentin Tarantino screened Male monarch Hu's 1971 wuxia that the mogul began a controversial spending spree in the east that led to his current controversial involvement with Bong Joon-ho'due south Snowpiercer. It's non hard to see why: Hu'south film is unusually epic for the genre, clocking in at over three hours, and fabricated movie house history by being the first Chinese film to win an honour at Cannes, missing out on the Palme d'Or but taking domicile the Technical prize.

A Touch of Zen is most notable nowadays as the template for Ang Lee's Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, being the 14th century story of an creative person, Ku, who encounters a beautiful adult female living in a rundown house with her elderly mother. In true wuxia fashion, nonetheless, she is not all she seems, and and so the story grows, until Ku realises that he is in the middle of a major dynastic war between rival factions. And as the story develops – effortlessly arresting elements of one-act and romance – so does the spectacle, increasing in scale and scope in means that would be unimaginable today.

It is these fight sequences that have endured, and although wuxia briefly fell out of favour before long after, information technology is piece of cake to see Hu'south influence on the hitting martial arts films of recent years. More than so than Crouching Tiger, A Affect of Zen casts a long shadow over the films of Chinese director Zhang Yimou, whose House Of Flight Daggers direct references Hu's film in its bravura bamboo forest sequence. But it is Hu'southward deadpan sense of the chiliad that keeps this astonishing film fresh, with its themes of justice and nobility, shot through with a strange spirituality that earns the movie its title in a sequence involving a pack of bouncing, kicking-donkey Buddhist monks. Damon Wise

7. The Raid

As a breathless and brutal martial arts thriller shot in Djakarta and directed by a Welshman, The Raid would already take been worthy of notation. That information technology is a film of precision and inventiveness, taking fight sequences into the realm of horror, slapstick comedy, even the musical, guarantees its place in activity-moving picture history. The plot is equally simple every bit its choreography is complicated. A police force unit sets out one morning to seize command of a tower block in Djakarta that has fallen into the hands of a gang. But non just any gang: this mob has kitted out the high rise with sophisticated CCTV and public accost systems monitored from a top-floor control room. The gang-lord, presiding over the CCTV screens, broadcasts a phone call to his tenants: "Nosotros have company. You know what to exercise." He doesn't hateful put the kettle on and cleft open the custard creams.

In the absence of much dialogue, the weapons practise the talking: guns, knives, swords, hammers. A human receives an axe to the shoulder, which is then used to yank him across the room. A refrigerator doubles equally a flop. The gang's virtually brutal member, Mad Domestic dog (Yayan Ruhian, who too served as i of the film's fight choreographers), acts every bit mouthpiece for the film's philosophy. Casting aside his firearms, he explains: "Using a gun is like ordering takeout." If that'southward the case, Mad Dog would merit a fistful of Michelin stars.

Some of the fight sequences are enclosed claustrophobically in hallways where the only option is to use walls as springboards, Donald O'Connor-style. Others, such equally a dust-up in a drugs lab, expand similar dance numbers. Evans'southward prime accomplishment has been to make a berserk adventure characterised by clarity. In contrast to most action cinema, the frenzy arises from the performers rather than the editing; no matter how frenzied things go, nosotros never lose sight of who is karate-chopping the windpipe of whom. Ryan Gilbey

vi. Ong-Bak

Hands and feet are one matter in martial arts; elbows and knees are quite some other. And afterwards seeing this Muay Thai showreel, yous'd put coin on Tony Jaa confronting any other screen fighter. Even in the scenes where Jaa isn't fighting anyone at all, merely going through some moves, he's awesomely formidable.

Ong Bak as a flick is fairly straightforward: metropolis baddies steal a village'due south Buddha head; a humble peasant goes to go information technology dorsum, individually crushing each adversary with his bare hands in the procedure. That's all it needs. Ong Bak's prime objective is to say, "Tin can you believe this guy?" and with the added notation that no special effects or stunt doubles were used, it more accomplishes information technology. In fight after fight, Jaa unleashes moves that exit you thinking, "That's gotta hurt", if non "That'south gonna require major cranial reconstruction". No holds are barred and few punches are pulled, merely rather than creature violence, you lot're left marvelling at Jaa's speed, technique and hurting threshold. The fights are skilfully staged, especially an exhilarating, iii-round barroom brawl that leaves no opponent or piece of furniture standing.

Jaa shows off his physical prowess in other ways, too, from an opening tree-climbing race to a Bangkok street hunt that sends him forth a hilarious set on course of buffet tables, market place stalls, children, cars, trucks, sheets of glass and hoops of barbed wire. He'south almost too much to believe, and Ong Bak acknowledges our incredulity past frequently rewinding the action to show us Jaa's moves in slow motion, as if to say, "Exercise y'all want to see that again?". Nosotros do. SR

5. The Matrix

Cocteau imagined the mirror as a gateway to another world in his 1930 film The Blood of a Poet, and it's a attestation to the durability of this paradigm that when it turned up once more in The Matrix, it had lost none of its attraction. The pic clocks upward a farther debt in its plot, which proposes that what nosotros perceive as reality is really a cosmetic facade constructed to conceal a terrible truth almost our existence. Neo, a computer boffin played by Keanu Reeves, is selected to bear the burden of enlightenment. Reeves's blankness in the part is perfect, mainly because Neo is required to display only those skills and qualities that are downloaded into his brain. Required to master jujitsu, he is just installed with the relevant computer programme. In no fourth dimension at all, he is pulling off those tricks from 1970s martial arts movies, where a human being can launch himself in a flight kick and somehow manage to fix a cocktail, read a short novel and fill out his tax render, all before his feet bear upon the ground.

The moving-picture show's Cocteau-esque concept is harnessed to some X-Files-style paranoia, merely it is the dazzling martial arts work that gives the picture its special lift. The directors, the Wachowski brothers, were already having ideas above their station when they came up with The Matrix (their only previous movie, afterward all, was the sweaty, claustrophobic thriller Bound). Information technology was the martial arts choreographer Yuen Woo-ping who helped them reach the side by side level.

The movie's fight sequences provide its purest source of pleasure for a number of reasons. Showtime, the violence doesn't come with redemptive overtones; it is played out for the thrill of the choreography, non the apprehension of injury or righteousness. Death is flippant, but it provides no moral kick. Second, the motion picture introduced a foreign new effect, much copied or parodied since in everything from Charlie's Angels to Shrek: a character freezes in midair while the photographic camera circles the tableau like a computer imagining a 3D representation of a 2D epitome. When the camera has completed its movement, the concrete motion of the scene resumes. Suddenly the humdrum vocabulary of the action film has been extended before our disbelieving optics. RG

iv. House of Flying Daggers

Watch the opening 20 minutes of House of Flying Daggers and it's not hard to see why the Chinese picked its manager, Zhang Yimou, to directly the opening ceremony of the Beijing Olympics. Even though the action unfolds within a reasonably sized brothel waiting room instead of a stadium, there'due south all the elements that Zhang would multiply by the thousands in 2008: traditional Chinese music, dancing, swathes of brightly coloured silk fabric, drummers and, of course, martial arts. It makes for a magnificent spectacle that'southward sets a loftier bar for the remainder of the flick. Fortunately, there's more dazzle to come up in this follow-up to Zhang's get-go wuxia film, Hero. Zhang'due south 2006 Curse of the Golden Flower concluded the trilogy, but for many the romantic, operatic however satisfyingly compact Flying Daggers represents the best of the three.

Set during the Tang dynasty, 2 police force captains, Leo (Andy Lau, best known for the thematically-not-different Infernal Diplomacy trilogy) and Jin (hunky Takeshi Kaneshiro) are searching for the leader of the Flight Daggers, a counterinsurgency group. They suspect bullheaded courtesan Mei (Zhang Ziyi) may be a secret member of the Daggers, and so Jin, posing every bit a citizen, busts her out of jail and goes on the run with her, pursued by Leo and numerous expendable officers. Dearest seems to bloom between Jin and Mei, simply no ane and nothing are equally they seem here.

Although the fights are terrifically choreographed by Tony Ching Siu-tung – specially a bamboo-forest hunt that tops Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon and a concluding mano-a-mano in the snow – judged confronting other classic martial arts films, Daggers is actually a little light on combat scenes. Indeed, the fighting is then stringently stylized it's more like dancing with knives. No affair: the love story may exist almost as schematic as the picture show's rigorous utilize of colour, yet the acting is so powerful from the core trio that deep emotional depth is created seemingly out of nothing. Leslie Felperin

3. Law Story

Although it was obvious at the fourth dimension, it seems strange now that Jackie Chan was originally clean-cut past at to the lowest degree i Hong Kong producer every bit a successor to Bruce Lee, the lithe master of martial arts whose style was well-nigh laughably serious in its grim-faced intensity. Subsequently a few tryouts in the genre, however, Chan took things in a much more comedic, just no less able-bodied route, which is why, later on breaking out in the Yuen Woo-ping classic Drunken Main, the one-time stuntman institute himself in Hollywood, adding light relief to The Missive Run in 1981.

Chan's Hollywood career, nonetheless, didn't pan out, and later a disappointment in 1985 with The Protector – a collaboration with neo-grindhouse director James Glickenhaus, perhaps not the most sympatico of all possible talents – Chan returned to Hong Kong to have matters into his ain hands, directing and cowriting Police Story, in which he played a disgraced cop who is forced to go undercover and clear his name afterwards being framed by drug barons.

Making a straight rebuttal of the Hollywood fashion of doing things (in his listen, sloppily and one-half-heartedly), Chan prioritised the fights and stuntwork, using the genre elements mostly as filler. Refusing to utilize a body double for every scene (bar one that involved a motorcycle), Chan began to earn his reputation as a fearless and pioneering action star. On this film alone, he was hospitalised with concussion, suffered astringent burns, confused his pelvis and was near paralysed past a shattered vertebrae. The resulting movie was a huge hit and spawned 5 strong sequels. Seen now, it seems remarkably direct given what was to follow – the cartoonish Rush Hr series – although Chan certainly must have enjoyed the irony of being embraced by Hollywood for a motion picture that is, substantially, a critique of everything it was doing incorrect. DW

2. Crouching Tiger, Subconscious Dragon

Why is Ang Lee's flick Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon such a sublime experience? Perhaps because every bone in your body tells y'all it shouldn't work. Information technology's a tranquil activity movie. Whoever heard of one of those? And information technology's a dear story with a kick: a kung-fu kick. It begins with the theft of a fabled sword, the Light-green Destiny. Every bit the sword is stolen, the camera takes flight along with the thief, for whom gravity is a restricting garment to be cast off at a moment'due south notice. The warrior Yu Shu Lien (Michelle Yeoh) gives hunt, skipping blithely across rooftops that glow silvery in the moonlight. When the pursuit gives style to combat, the rule book of activeness movie theatre is not just discarded but sliced to ribbons. For viewers likewise young to remember, the shock of seeing a Sam Peckinpah shoot-out back when tiresome motility was an innovation rather than a nasty virus, and so the sight of these warriors levitating calmly to nosebleed-inducing heights will provide something of that aforementioned liberating jolt.

The midair skirmishes of martial arts movies were brought to mainstream audiences past The Matrix, and Lee enlisted that motion-picture show'southward choreographer, Yuen Woo-ping (who afterwards worked on Impale Beak and Kung Fu Hustle), to take that style even further. The resulting fight routines evoke Olympic gymnastics, break dancing and those cartoon punch-ups where ane of the Tasmanian Devil's limbs would sally briefly from within a frantic cyclone. And if Yu occasionally steps on her opponent'due south foot, she's not fighting dirty – it's just the but fashion of ensuring that the battle remains at ground level.

For all the finesse of the choreography, the activity sequences would be superficial without the emotional weight Lee brings to the picture, notably in the largely unspoken tenderness between Yu and her fellow warrior Li Mu Bai (Grub Yun Fat). As a director he doesn't differentiate betwixt the manner he shoots tenderness and violence. In his hands, a honey scene can come to be fell, with a man's claret forming a fork across his lover'due south chest as they encompass, while a struggle between opponents in the forest treetops, with the supple branches doubling as nests, catapults, rungs and bungee ropes, achieves a sensuous serenity. RG

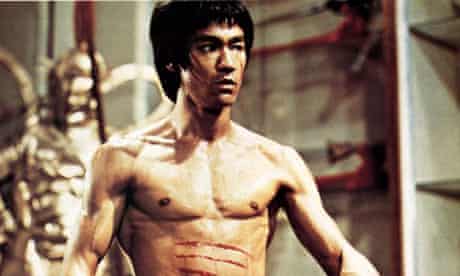

1. Enter the Dragon

Bruce Lee purists may or may not agree that Enter the Dragon is his greatest movie. But this is the 1 that has passed into legend: it was the jumbo box function smash of 1973 and the nearly famous film of that unrivalled martial arts superstar who had died the summer before its release of a cerebral reaction to painkillers. He shared with James Dean the grim distinction of actualization posthumously in his well-nigh famous moving picture. After a career as a child star in Hong Kong movie house – almost the Macaulay Culkin of his day – and a spell on TV's The Green Hornet, Lee exploded into action pictures that were simply and so popular and profitable that Warner Brothers agreed to make Enter the Dragon, with Lee every bit star and coproducer: Hollywood's kickoff martial arts movie. Robert Clouse directed, and the script was past Michael Allin, who wrote the Isaac Hayes film Truck Turner. Lalo Schifrin composed the music.

Bruce Lee was possessed of boggling concrete grace, balletic poise, lethal speed and explosive power. He was a primary of kung fu, judo and karate, and is considered the spiritual godfather to today's mixed martial arts scene. He was not a big man, and so his presence was better captured past the camera lens. Moreover, he had a delicately handsome, almost boyish face and had a charm and verbal fluency every bit he expounded his Zen theories of gainsay in interviews, something more like dynamic motivational philosophy than whatsoever fortune-cookie platitude. Lee had a presence and charisma comparable to Muhammad Ali, and that was possibly never better captured than in Enter the Dragon. Perhaps only Jackie Chan now rivals him as an Asian star in Hollywood – and Hollywood has not shown much interest in promoting an Asian-American A-lister since Enter the Dragon.

Lee plays a Shaolin primary who is recuited by British intelligence to enter a martial arts tournament underground. This event is being run past a sinister megalomaniac called Han who is suspected of involvement in drugs and prostitution. Lee has a personal beefiness with Han, whose goons terrorised and attempted to rape Lee's kid sister – she committed suicide rather than submit. He shows upwardly at the island with a couple of American fighters: Williams, played by Jim Kelly, provides some Shaft-style street cred while Roper, played by John Saxon, is a playboy type who is shut to the James Bail template. In truth, of form, information technology is Lee himself who is the James Bond, but he is no womaniser. Bruce Lee has a monkish purity and spirituality, with a light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation-like focus on exposing Han – and of course kicking ass.

The look of the movie is exotic and extravagant, especially its inspired hall-of-mirrors showdown, with Lee sporting the weird, most tribal slashes across his midriff. His strange, animal quavering cry and piercing gaze are entirely unique. Just what makes Enter the Dragon outshine the rest is the serene, almost innocent idealism of Lee himself. In the opening scenes, Lee speaks humbly to the anile Abbot at his temple, coolly takes tea with the British intelligence primary Braithwaite, and interrupts their conversation to instruct a teenage boy in martial arts. When this young hothead is easily bested in combat, Lee says to him with inimitable seriousness: "We demand emotional content – not anger." It is the philosophy of this martial arts archetype, and its unique star. Peter Bradshaw

More Guardian and Observer critics' acme 10s

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/film/filmblog/2013/dec/06/top-10-martial-arts-movies

0 Response to "Martial Arts Film Fight Way to Top of Building"

Post a Comment